Understanding and predicting the effects climate change, habitat loss, and other human disturbances on natural populations is one of the grand challenges for today’s natural scientists.

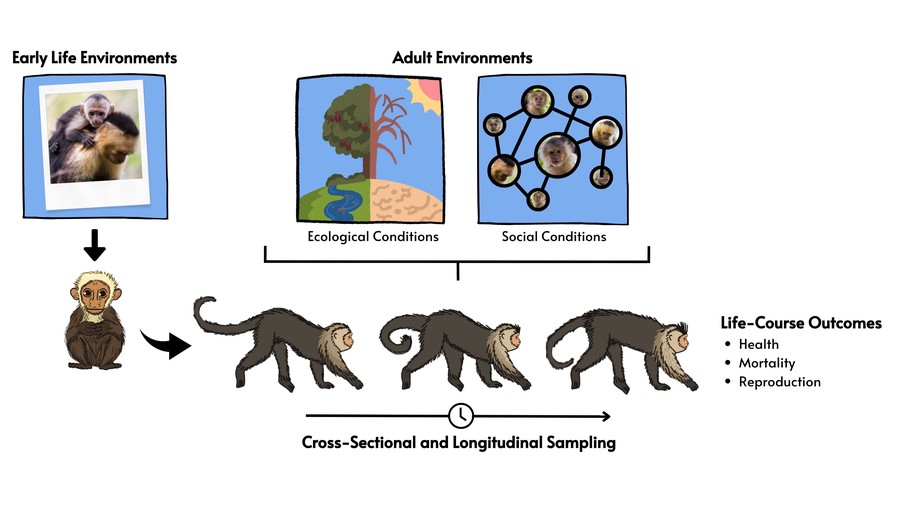

My research is in the broad area of behavioral responses to changing environments, both ecological and social. We still do not fully understand the limits of behavioral flexibility or whether adaptive responses will be sufficient to keep pace with rapidly changing environmental conditions. These gaps in our understanding motivate the goals of my research: to shed light on the limits, consequences, and evolutionary roots of flexible responses to environments that change in time or space.

I study natural primate populations. I am a co-director of the Santa Rosa Primate Project in Costa Rica’s Área de Conservación Guanacaste, where my work focuses mainly on white-faced capuchins but also includes spider monkeys and howler monkeys. The capuchins of this population are the subjects of one of the longest-running continuous primatology field studies in the Americas. I have been closely involved in research on this capuchin population since 2006, and I now co-direct research on capuchins at the site with Amanda Melin and Linda Fedigan at the University of Calgary, and Katharine Jack at Tulane University.

I have longstanding collaborations focused on savannah baboons in the Amboseli ecosystem of East Africa and black-and-white colobus in Ghana. I also do comparative research with the Primate Life History Database.

Interests

- Behavioral ecology

- Life histories

- Aging

- Biodemography

- Global change

- Primates

Education

PhD in Biological Anthropology, 2014

University of Calgary

MA in Biological Anthropology, 2008

University of Calgary

BSc in Biology, 2002

California Institute of Technology